"May you live in interesting times." - ancient Chinese curse, supposedly

For generations of us growing up with the constant presence of digital communication technology, “interesting” doesn’t even begin to cover it.

Our near-limitless access to information is a boon that our ancestors could have never dreamed possible. And while this deluge of data has revolutionized how we share ideas, it has also created a “wild west” of uncertainty when it comes to online sources. Anyone can pretty much publish anything, and discerning good sources from bad can get tough.

Don’t get me wrong, the democratization of the digital age is overall a great thing, but it resists the sort of gatekeeping that might otherwise bolster the validity of content. In other words, no one’s filtering the info – the “bad” and the “good” float along the digital current with the same visibility. It becomes the user’s job to judge what’s true, and for writers and researchers, it adds a new layer to information gathering.

Digital Information Literacy: How do you know what you know?

“Literacy” basically means a competency in communication, and it is a transformative power for individuals and for societies. The ability to wield contemporary media can ignite revolutions and topple empires.

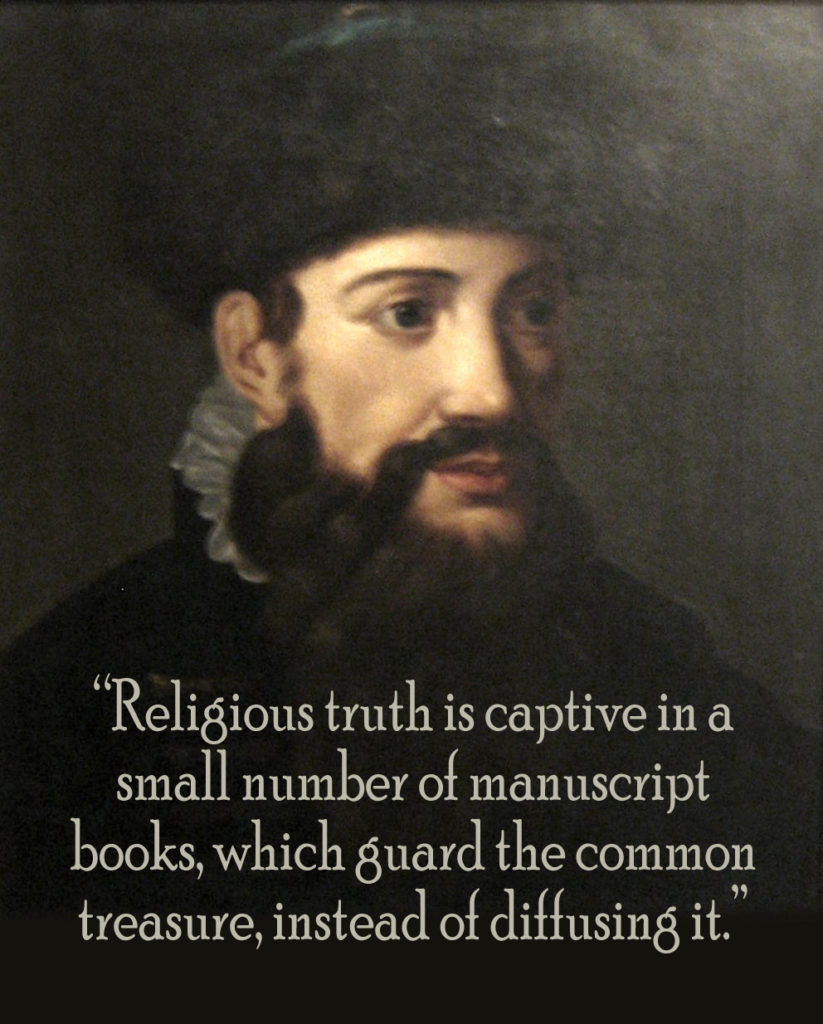

Take Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press, for example – a huge technological leap for literacy, and one that religious contemporaries like Martin Luther were smart enough to exploit. The Protestant Revolution in 16th century Europe was made possible by the printing press. It brought the written word to the masses, generated a common literacy, and disrupted centuries of religious authority. (Haile, 1976) Like the internet, it altered the nature of public knowledge and forever changed the dynamics of the control and access of information.

Gutenberg’s press made Martin Luther one of the first “influencers” of western history. Luther recognized the power of a new media modality to build his following – basically the PewDiePie or Kylie Jenner of his time. If the consumption of mass media brings knowledge, the creation of it brings powerful levels of influence. And if Spiderman comics taught us anything, it’s that with great power comes great responsibility!

Literacy = liberated knowledge, decentralized influence, and empowered individuals. Pretty good stuff. And our concept of what literacy means is something that changes alongside society, culture, and technology. To utilize language and media in the age of smartphones and globalized networks thus requires new “literacies” as we leap ahead of Gutenberg in terms of mass communication. Our informational context has exploded, and the requirements to navigate it have become increasingly complex.

Where does that leave us? Increasingly, scholars are concerned about the learner’s and researcher’s ability to parse data in a way that serves professional and academic interests. Let’s be real, most people know that the internet cannot be readily trusted, however this understanding doesn’t automatically translate to good research habits. Kevin Arms in the video here discusses a few examples of students failing to recognize “fake news.” Librarians like Arms are well-familiar with the importance of information literacy, and have been at the forefront of this issue.

In a survey study from 2012, teachers reported that 94 percent of their students were “very likely” to use an internet search engine in their research, and a chief concern was over the “difficulty many students have judging the quality of online information” (Purcell et al, 2012). Most students grew up with the internet and social media, so they adapt

easily to these platforms – AKA, they have strong digital literacy. They also know not to trust everything they see. When Project Information Literacy surveyed students on their views of online algorithms, they cited “shaping content,” “reinforcing inequalities,” and “not seeing the same reality” as major concerns (Head et al, 2020).

This understanding of algorithmic bias in our online activities is one starting point for thinking about informational reliability. It reminds us to think twice about data we come across both in targeted research and in incidental use. Many familiar digital platforms are, in a sense, literally designed to confirm what we already think, which “is the reason many people use them in the first place” (Seneca, 2020).

Algorithms aren’t the only thing to worry about. The proliferation of bad info (or “fake news”) has changed the entire information landscape. It can range from shallow conspiracies to misleading biases to fully choreographed disinformation campaigns. And it has proven to be a potent and insidious force. In one MIT study, researchers found that “falsehood diffuses significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth, in all categories of information, and in many cases by an order of magnitude” (Dizikes, 2018). In other words, “fake news” has a unique power and reach on social media, like one big game of telephone, taking us farther and farther from the truth the more the story spreads.

These researchers were looking at Twitter, but YouTube is another common research source plagued by crappy content. For example, pseudo-science has shown a potential to spread easily on the site. One investigational report found that YouTube’s algorithms were driving millions of viewers to videos about climate change denial (AVAAZ, 2020), and it’s not always easy to discern good and bad sources solely based on their appearances.

Who do you trust?

To reiterate, when we’re talking about the ability to gather and understand ideas and data, we’re talking about “information literacy.” This is one of the vital components to any kind of research, and it takes on a special importance when it comes to the digital realm.

Information literacy empowers people in all walks of life to seek, evaluate, use and create information effectively to achieve their personal, social, occupational and educational goals. It is a basic human right in a digital world and promotes social inclusion in all nations.” (UNESCO, N.D.)

A “human right” perhaps, but not always an easy skill, even as we all grow accustomed to the daily presence of these media. Digital literacy may now be second nature to us, but a problem still lies in a gap in critical thinking, as argued by library science professor Jamie Gregory. She suggests a dedicated education on subjects like online conspiracy theories and other stories that seem authoritative, but have in fact been debunked or retracted. (2019). This may be an extra challenge for educators, but it can help teach students better approaches to research.

High school teacher JoAnn Gage tackles the problem by adding a digital media literacy component to essay assignments, and by quizzing students on their ability to identify varieties of online misinformation that she also demonstrates in class (2018). How well would you do on such a quiz? Can you tell which of the stories below are real, and which are not?

[hover id=”177″]

[hover id=”181″]

Ultimately the big question is this: how good are we at differentiating fact and fiction on the web? What is the skillset? A behavioral science study tried to measure the ability of participants to recognize “fake news” in four different literacy contexts: media literacy, information literacy, news literacy, and digital literacy. Data was collected via online survey, using different questions to measure participants’ grasp on each literacy type. At the conclusion, information literacy was the only type of literacy to demonstrate a clear correlation with an ability to discern real or fake information (Jones-Jang, 2019). The significance here is that simply knowing how to use technology (digital literacy) or understanding different types of outlets (media literacy) is not enough.

Students and researchers exist in a complex information environment, and this complexity will affect not only the quality of their writing but also the nature of their interests. While educators do their best to nurture good habits, part of the problem here may be that students are taught information literacy in a highly controlled environment, rather than one that represents real life. “In this bubble, students may be asked to engage with intellectually stimulating topics and might even emerge ready for college classwork, but they are often unprepared for the nonfiction demands of adult life,” argues an article published in the Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. (Kohnen, 2018). Rethinking educational approaches and giving people effective tools for navigating digital space is one way to nurture critical research habits.

Teaching the ethical standards of reporting can be another approach to helping writers and communicators understand the values to look for in content writing, such as accuracy, neutrality, accountability, and transparency (SPJ, 2014). In this fragmented era where “fake news” has come to mean any source that is disagreeable, it’s important to not only develop empirical tools but also a value-set – what makes “news” news? By bridging the gap between media trust and media transparency, we can reaffirm standards that separate fact from fiction, and encourage outlets to hold accountability for what they put out into the world.

It may often feel like this brave new online world is hopelessly muddled, but these are just the growing pains of an evolving modality. We won’t find all the answers right away, but we can start by becoming better equipped to navigate the messy minefield of online information and passing those skills on at every opportunity. ~~~

REFERENCES

- AVAAZ. (2020, January 16). Why is YouTube Broadcasting Climate Misinformation to Millions. https://secure.avaaz.org/campaign/en/youtube_climate_misinformation/

- Dizikes, P. (2018, March 8). Study: On Twitter, False News Travels Faster Than True Stories. MIT News. https://news.mit.edu/2018/study-twitter-false-news-travels-faster-true-stories-0308.

- Gage, J. (2018, November 3). Rethinking the Persuasive Research Paper: Combating Fake News, Media Bias and Polarization of Ideas Through Teaching Media Literacy and Researching Opposing Sides. Iowa Council of Teachers of English. https://iowaenglishteachers.org/2323/teacherwritings/rethinking-thepersuasive-research-paper-combating-fake-news-media-bias-and-polarization-of-ideas-throughteaching-media-literacy-and-researching-opposing-sides/.

- Gregory, J. (2019, November 6). Teaching Disinformation Literacy. The Office for Intellectual Freedom of the American Library Association. https://www.oif.ala.org/oif/?p=19111.

- Fora.tv. (2010, 25 January). Thomas Sowell: Global Warming Manufactured by Intellectuals? . https://youtube/rweblFwt-BM.

- Head, A.J., Fister,B., & MacMillan, M. (2020, January 15). Information Literacy in the Age of Algorithms. Project Information Literacy. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED605109.pdf.

- Joe Scott. (2018, April 23). Busting Climate Change Myths | Answers With Joe. . https://youtube/sZB1YtQtHjE.

- Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T., & Liu, J. (2019, August 28). Does Media Literacy Help Identification of Fake News? Information Literacy Helps, but Other Literacies Don’t. American Behavioral Scientist. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219869406.

- Kohnen, A.M., & Saul, E.W. (2018). Information Literacy in the Internet Age: Making Space for Students’ Intentional and Incidental Knowledge. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 61( 6), 671– 679. https://doi-org.remote.baruch.cuny.edu/10.1002/jaal.734

- Pearson, E.C. (1871). Gutenberg and the Art of Printing. Boston, Noyes, Holmes, and company. pp. 8-9.

- Perdew, L. (2016). Information Literacy in the Digital Age. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com.

- Purcell, K., Rainie, L., Buchanan, J., Friedrich, L., Jacklin, A., Chen, C., & Zickuhr, K. (2012, November 1). How Teens Do Research in the Digital World. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2012/11/01/how-teens-do-research-in-the-digital-world/.

- Quartz. (2018, January 15). Five Ways to Spot Fake News. . https://youtube/y7eCB2F89K8.

- Seneca, C. (2020, September 17). How to Break Out of Your Social Media Echo Chamber. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/facebook-twitter-echo-chamber-confirmation-bias/.

- Society of Professional Journalists [SPJ]. (2014, September 6). SPJ Code of Ethics. https://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp

- TEDx Talks. (2017, November 28). Information Literacy | Kevin Arms | TEDxLSSC. . https://youtube/3BAfs_oDevw.

- UNESCO. (N.D.) Information Literacy. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/access-to-knowledge/information-literacy/.

Published by